True Strategic Autonomy Requires Improved Domestic Supply

17 March 2023

Achieving a successful clean energy transition while retaining control over necessary critical resources cannot happen if EU Member States continue to avoid the inconvenient discussion on the importance of domestic production.

This week the European Commission is set to unveil the Critical Raw Materials (CRM) Act to provide a framework to tackle the issue of resource dependencies in pursuit of the Green Deal policy objectives. However, the success of this framework hinges on the willingness of Member States to move beyond quick fixes and to make hard choices on the trade-offs between security of critical resources and Europe’s long-term environmental agenda.

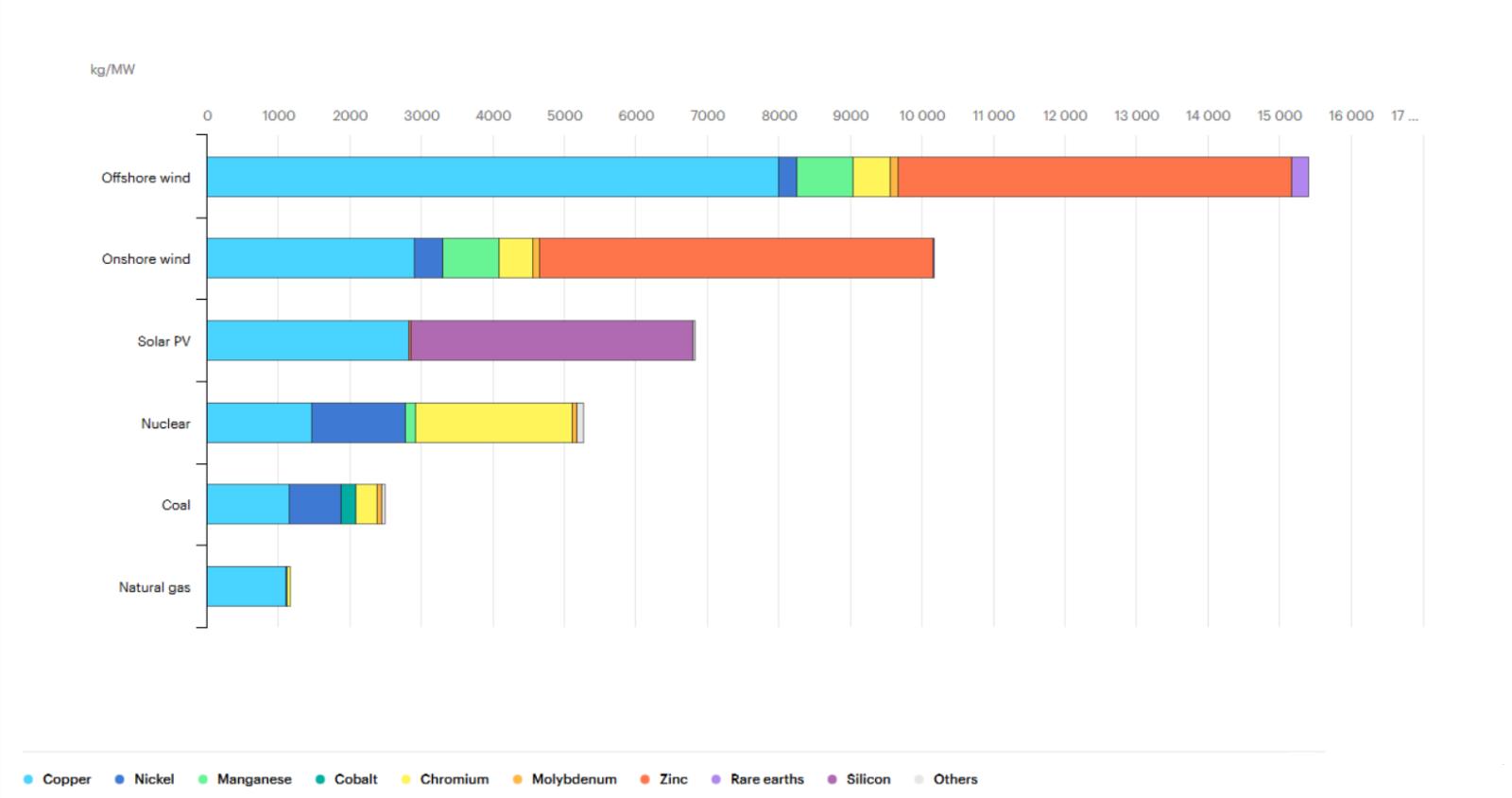

European policymakers have long been aware that action needs to be taken to ensure the stability of its domestic supply of CRMs. These resources, which include amongst others rare-earth elements (REEs), lithium, silicon, and zinc, are crucial for the development of green energy solutions, such as for solar PVs, and off-and-on-shore wind turbines, as well as electronic vehicles (Fig 1). However, the vast majority of CRMs are currently sourced from China, which holds a near monopoly over the refinement of REEs, and accounts for over half of the production of processed cobalt and lithium.

Table 1: Minerals used in clean energy technologies compared to other power generation sources

Source: International Energy Agency

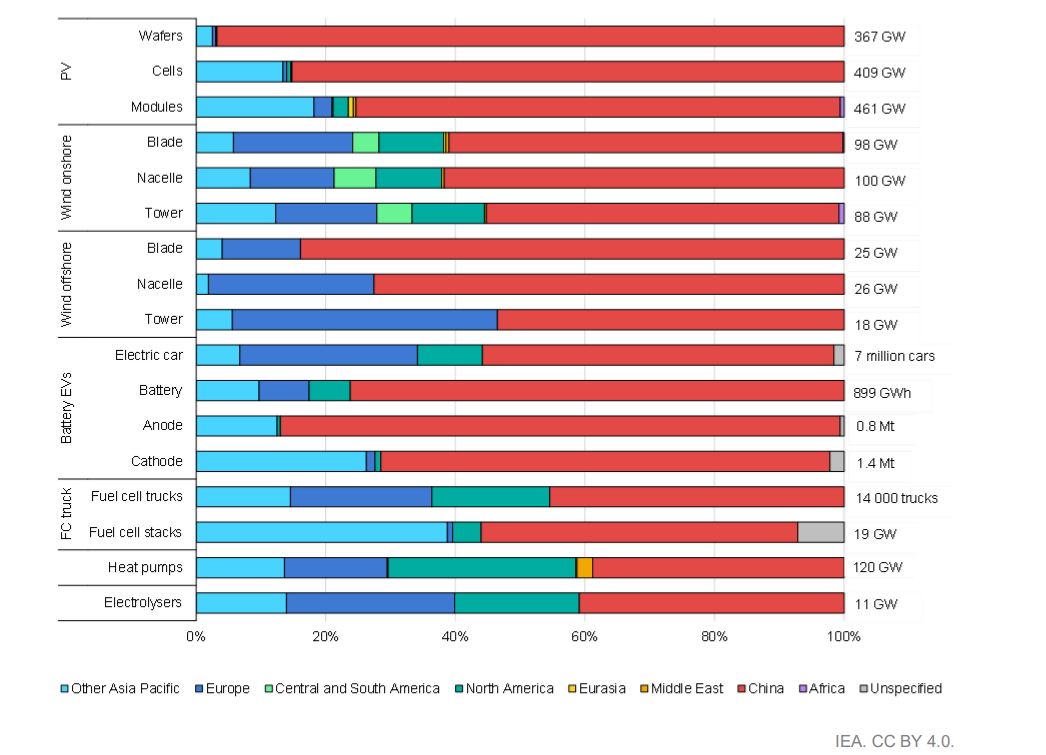

Beyond its borders, the Asian country is investing heavily in the extraction of strategic resources, further cementing its leadership position. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which produces 70% of the global cobalt supply, Chinese companies own 15 out of the 17 mining operations. China’s dominance in the field of CRMs has facilitated its rise as a top producer of clean energy technology. For years, Beijing has aggressively subsidised its clean energy industry and manufacturing, resulting in a market share of 75% to 90% of every stage of the production process (Fig. 2). Not to mention the continuing use of Uyghur slave labour in the Xinjiang region, which is extremely rich in polysilicon supply.

Despite the existence of adequate deposits within the continent, the EU lacks any meaningful domestic production of CRMs. The economic bloc stands for less than 5% of global production while our industries require around 20% of global supply. This is not sustainable. Global consumption is set to increase substantially over the years, especially within the EU, which is investing heavily in sustainability. World Bank estimates show that demand for minerals such as graphite, lithium or cobalt will increase five-fold by 2050.

Fig. 2 Regional shares of manufacturing capacity for selected mass-manufactured clean energy and components, 2021

Source: International Energy Agency

The current EU strategy, focusing on strengthening the circular economy and diversifying supply chains, provides a good long-term framework to tackle the issue. However, Member States should take the lead in the discussion of how to operationalise this in the short to medium-term, as serious obstacles remain.

While efforts to strengthen the circular economy and recycling practices will undoubtedly aid the EU, this will be far from sufficient to ensure true strategic autonomy. Recycling CRMs outside of the production process is often economically unviable or downright impossible. The end-of-life recycling rate of silicon metal, germanium and REEs, all crucial in the development of clean energy technologies, remains extremely low, and will thus not solve the EU’s dependence on Chinese resources.

Diversifying the supply chain of CRMs can partially remedy the shortcomings of recycling and avoid the issues related to domestic production. While this option is promising and should be explored, it has a number of caveats. Exporting these industries to friendly nations abroad (i.e., friend-shoring) will not prevent the inherent risks attached to stretched-out global supply chains. Furthermore, research has highlighted the negative economic consequences related to friend-shoring practices, as well as the practical issues of reconfiguring global supply chains in the short to medium-term. Lastly, the environmental as well as ethical implications of moving mining operations to areas with often poorer environmental/labour standards should not be underestimated.

The issues related to recycling and friend-shoring show that true security of critical resources can only be attained in combination with an increased domestic supply of CRMs within Europe. Member States must resist the temptation to take the path of least resistance and instead address the issue head on. Many governments are nervous about openly supporting new mining projects given the potential local backlash or time restraints due to long permitting processes. However, the solution remains entirely in their hands as national governments are the ones to actually push for optimising these processes and increase domestic production in Europe. The length of the permit granting procedures must be curtailed so that we see actual progress by the end of this decade. An increase in domestic production and improved predictability of supply can also bring the EU closer towards the additional goal of improving its critical materials stockpile in the long run.

Simply put, the EU cannot afford to repeat the same mistake it made on Russian energy imports with critical materials supply. If Europe wants to weave a convincing narrative about strategic autonomy, perhaps it would be best if it worked towards genuinely improving its self-sufficiency in key areas.

ENJOYING THIS CONTENT?