China’s Digital Currency: Mao Would be Proud

14 January 2021

You’ve got to hand it to the Chinese authorities – there`s never a dull moment. In late 2020, a lottery was organised in the city of Suzhou for the allocation of thousands of online wallets, each containing 200 digital yuan (25 euro). The lottery was one of the many pilot experiments organised by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) to test how China’s central bank digital currency would perform both online and offline.

On the face of it, this is a noble pursuit by a government providing essential services to its citizens. The World Bank estimates that China has one of the highest number of people who lack access to a bank account. The PBOC wants to provide a state-backed digital equivalent of the yuan which will be fully operational in late 2021 or early 2022. However, the government isn’t actually opening new opportunities – it’s desperately trying to catch up with the private sector.

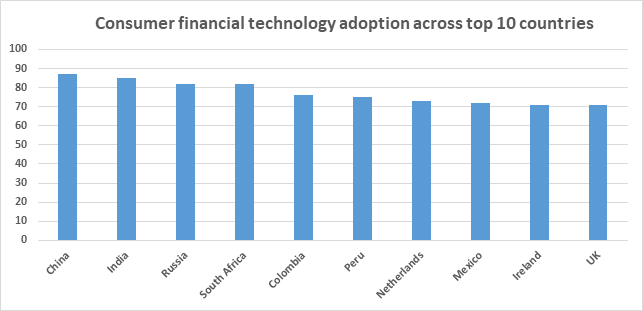

In the last decade, the Asian country made a silent transition to a near cashless society. Payment systems designed by digital giants Alibaba and Tencent essentially leapfrogged the card-based services and started a revolution in financial transfers and retail. China currently tops the global ranking of financial technology (FinTech) adoption globally, with 87 % of its mobile users having access to innovative services. FinTech refers to all kinds of technology-enabled innovation in the financial sector. Plastic cards are not in vogue anymore – QR codes and FinTech apps make the money go round in China.

Fig. 1 Source: E&Y | Martens Centre

Widespread mobile applications Alipay and WeChat Pay dominate the mobile payments market in the country, with trillions of euro worth in annual transactions. When it comes to personal data, the reputation of these private apps is murky. In early 2021, the US President signed an executive order banning transactions with eight Chinese software applications (Alipay and We Chat Pay included) due to potential snooping of sensitive data.

The Chinese Communist Party isn’t too happy with the fact that private companies operate the bulk of transactions within the country and that so much money is transferred from traditional banking accounts to electronic wallets. The PBOC is also eager to cut the costs of maintaining traditional banknotes, and also being able to efficiently track money flows within China.

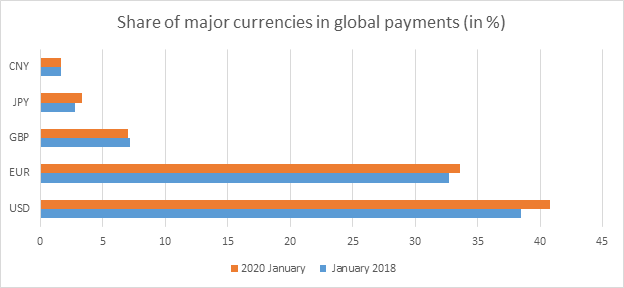

An additional aim for Beijing is increasing the international appeal of its currency. The yuan’s annual share of global payments cleared on SWIFT hovers around 2%, which is meagre compared to the sway of the dollar, euro, and pound sterling. If China is the first country to launch a digital currency, it will make the headlines, but that doesn’t mean the yuan’s inherent problems will go away. Foreign investors are subject to specific financial restrictions, while Chinese authorities have often intervened in capital markets and been criticised for currency manipulation. Global investors are not going to judge a currency only by its shiny new cover. Still, Chinese leadership hopes that in the long run, a digital yuan might pressure the dominance of the US dollar and become the currency of choice for partner countries in Asia.

Fig. 2 Source: SWIFT

USD = US dollar, EUR = Euro, GBP = British pound, JPY = Japanese yen, CNY = Chinese yuan

Interestingly, the biggest prize here may not be the currency’s strength. Recent investigations report that Chinese regulators have persistently bullied Ant Group (parent to the Alipay app) to share their valuable troves of consumer-credit data they have been accumulating from their customers. The recent public disappearance of Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, certainly raises additional eyebrows. A few months ago, Ma publicly stated that traditional Chinese banks operate with a ‘pawn shop’ mentality.

Obviously, Chinese pawnbrokers and their political overlords are in a hurry. The state wants to reduce the dominance of private actors in the digital payment space. Policymakers in Beijing are also concerned that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin or Ethereum will grow in appeal for Chinese users, who may migrate funds towards decentralised and anonymous digital tokens. In essence, with its digital yuan, the Chinese state aims to develop the perfect anti-thesis to cryptocurrencies – highly centralised and completely prone to state surveillance.

It seems that China’s digital currency would tick all the right boxes – reining in private companies, tracing financial flows, and boosting the international appeal of its national currency.

The mass adoption of the digital yuan will make every transaction in the country potentially transparent and traceable. This would be an additional step in Xi Jinping’s blueprint for societal management through state-backed digital tools. Monitoring of digital financial flows can also be bundled with China’s nascent social credit system as a mechanism for rewarding and penalising individual behaviour. It seems that China’s digital currency would tick all the right boxes – reining in private companies, tracing financial flows, and boosting the international appeal of its national currency. Indeed, Chairman Mao would have been proud.

European policymakers shouldn’t underestimate these developments. Within the EU, Sweden is one of the few experimenting with the creation of a digital currency, while this topic isn’t even on the agenda in many European capitals. The European Central Bank (ECB) has launched a public consultation on the idea of creating a digital euro, but Frankfurt is years behind on an actual project. Europe doesn’t need to race ahead to beat China in creating a digital currency, but we should be wary of yet another domain in which the Chinese are taking the lead.

An in-depth Martens Centre research study shows that the EU is currently lagging behind when it comes to FinTech services and innovative financial products – all the hot developments are happening in Asia or the US. Add in AI research, telecommunications patents, or development of various technological standards internationally, and you’ll see the EU being dwarfed by China in many of these domains.

The EU is best positioned to pioneer a global standard for a secure digital currency, which will be complementary to euro banknotes. The ECB has the resources and technical capacity to develop a privacy-proof digital euro equivalent, which will be a natural next step in the digitalisation of the European economy. An ECB-designed digital euro should not be launched overnight, and should go through rigorous tests for its durability and state of the art privacy design. It could serve as a tool for financial inclusion of citizens who are operating outside conventional banking services and also increase personal convenience when dealing with financial transactions. Moreover, unregulated payment solutions or third-country financial applications are already mushrooming, which creates specific long-term risks and vulnerabilities. Like it or not, fundamental change is coming within retail, e-commerce and finance across Europe, and EU policymakers must be prepared to provide trustworthy alternatives.

In the coming years, we will witness increasing cyber warfare globally and a relentless race for technological leadership. The European Union simply cannot let digital authoritarians from the East dominate technological standards, or become unrivalled to pioneer new tools for monetary policy which carry the stamp of the Chinese Communist Party.

ENJOYING THIS CONTENT?