Is Slovakia heading towards a political earthquake?

26 February 2019

One year ago, Slovakia was shaken by the brutal murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová. Prior to his untimely death, Kuciak was working on the links between the Italian mafia and Slovak government officials, focusing on the misuse of EU funds.

In particular, Kuciak was working on the case of an oligarch who has, time and again, emerged from various scandals unscathed simply because he had “buddies” in the government, the police, and the prosecution. Now, all of the evidence is pointing to the conclusion that the oligarch is behind the murders. The outcome of this investigation could bring results that might cause a major earthquake throughout the Slovak political scene.

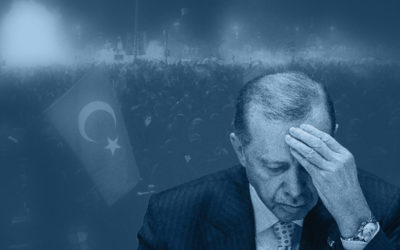

The socialist government, who is responsible for the current state of the country, is seen as an unbending force that is taking the country in the wrong direction, most notably for its failure to modernise the country, for its complicity in corruption, and for the controversial declarations made by former prime minister of Slovakia, Robert Fico, regarding Slovakia’s ambition to be among the core members of the EU. After its successful EU presidency, Slovakia enjoyed a solid pro-European image when compared to other Visegrad countries.

Today’s image of Slovakia is largely that of a corrupt-ridden country. In the latest Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index, Slovakia was ranked as the sixth most corrupt country in the EU. Slovakia has become a country where journalists, civic activists or ordinary citizens who expose corruption scandals are intimidated or, in the worst cases, silenced. Presently, Slovakia is in the grip of the kleptocrats, and after almost 15 years of EU membership, the foundations of democracy and the rule of law are still very fragile.

The murders of Kuciak and his fiancée have mobilised Slovaks to take to the streets and protest under the slogan “For a Decent Slovakia”. These protests were the largest rallies since the fall of Communism. The gatherings eventually led to the resignations of Prime Minister Fico, the minister of the interior and the president of the police force.

Nevertheless, Slovakia has not yet witnessed any genuine policy changes. Fico’s puppet has since been appointed Prime Minister and Fico himself has since escaped from politics by running to be a judge of the Constitutional Court. By being appointed as a new president of the Court, Fico would obtain 12 years of immunity and a status that would allow him to review the constitutionality of laws and measures that his own government drafted and pushed through parliament.

The Socialists’ coalition partner, Andrej Danko, a nationalist and the parliament’s speaker, has a different passion – he loves the Kremlin and its regime, and is openly critical of the “uselessness” of sanctions against Russia. He is a frequent guest of Chairman of the State Duma who is on the EU sanctions list.

After US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo concluded his visit to Slovakia, Andrej Danko flew to Sochi to meet Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov, where he stated that “[Slovak] politics should not, as it had been under Communism, be oriented to only one side, and that we should talk to both the Eastern and the Western countries.” That sounds familiar: In 1990, Slovak politicians remained undecided regarding the anchoring of the country towards the West, which resulted in the exclusion of Slovakia from EU and NATO accession talks.

This year, Slovakia is celebrating its 15th year as a member of the EU and NATO and the 30th anniversary of the fall of Communism. These milestones are a testimony to Slovakia’s failures, but also to its ability to rise again and realign its course to the right path.

In two weeks, Slovakia will be put to the test in terms of maintaining democratic process and on its ability to return to the right path, through the presidential elections. Fico’s presidential candidate will be European Commission Vice President Maroš Ševčovič, who still recently had the ambition of leading the European Socialists into the European Parliament elections in May.

Last week, however, Fico and his SMER party blocked a parliamentary vote on the appointment of judges to the Constitutional Court. As a result, Slovakia has been plunged into a constitutional crisis – the Constitutional Court is left with only four sitting judges, instead of its normal composition of 13.

Fico has blocked the election of new constitutional judges because he fears that even if he were to be elected by Parliament, President Kiska would not appoint him to the Constitutional Court as its member, let alone its chairman.

It seems that he is waiting for a new president ‘of his choosing’. The problem is that Maroš Ševčovič has been avoiding the question of whether, if elected President of the Republic, he would appoint Robert Fico to the Constitutional Court.

What is at stake in this case is not Ševčovič as a person, but rather the future of Slovakia. It is a question of what principles will prevail in Slovak politics: Will it be those of liberal democracy with its checks and balances, or will it be an even further concentration of power in the hands of a modern-day kleptocracy?

Last Thursday, peaceful demonstrations took place in several Slovak and European cities in memory of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová. Let’s hope that this encourages all Slovak democrats to vote in the upcoming presidential elections with a mindfulness of the very needed opportunity to realign with the path of justice, morality and decency in public life to be restored.

ENJOYING THIS CONTENT?